Australian geopolitics analysed by Dan Pagoda, expert of Australian international affairs and former policy advisor.

Speaking about Australia’s geopolitical outlook, the topic is often reduced to the question: « Rely on China for powering its economy or lean on the US for defence? »

The issue has had renewed focus under the administration of US President Donald Trump, whose antagonism towards China has shone the spotlight a little brighter on Australia and where it stands with the economic powerhouses. It has been suggested that Australia has started to pursue a more isolationist foreign policy, partly perhaps a result of seemingly being torn between the warring US and China.

Just as it would be ill-advised to distil Australia’s geopolitical outlook to this one question, so too would it be wrong to confuse isolationism with independence. Rather than seeking to isolate itself from the US or from China, Australia continues to assert its own independence and work towards a point where the question will not have quite so much prominence. Accordingly, while US foreign policy has taken a decidedly isolationist approach, giving rise to suggestions by several commentators that American hegemony is on the way out, Australia is not following the same path. Instead, it is increasingly dancing to the beat of its own drum, making clear it is no one’s lapdog to be taken for granted.

Australia in the world

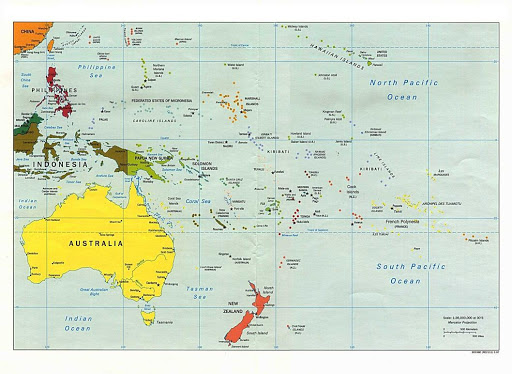

Asia. Asia Pacific. South Pacific. Australasia. Oceania. Which is it? Australia’s geographic place has never been an easy one to define. For its part, the Australian Government has in recent years taken to using the word “Indo-Pacific” to describe its strategic place on the global map. The nomenclature is important: previous iterations of its foreign policy placed heavy emphasis on the broader “Asia-Pacific”[1]. “Indo-Pacific”, meanwhile, brings the focus closer to home.

The realignment is perhaps best reflected in Australia’s overseas aid program which is now heavily directed to its own backyard. In 2015, then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull appointed the country’s first minister for international development and the pacific, firmly moving the focus closer to home. While the overall aid budget has fallen to just 0.2% of GNI, well below the 0.7% UN target, aid to the pacific region has remained largely unaffected.

It would be easy to discount Australia as a wannabe player on the world stage, interested solely in those issues that impact it directly with a decidedly inward focus. The reality, however, could not be further from the truth. The island nation continues to have a global presence. In recent years it has won two rotating seats on United Nations council, first the Security Council and later the Human Rights Council. Together with the US, the United Kingdom, Canada and New Zealand, it is a member of the exclusive Five Eyes intelligence sharing group, the world’s oldest intelligence partnership[2].

Australia’s defence forces continue to engage in missions far from the country’s shores. It was one of the first countries to commit troops as part of the war on terror and had boots on the ground in Afghanistan just a month after the 9/11 attacks where some 200 troops remain, half a world away from Australia. And while officially Australia’s aid budget is focused on its own region, the country continues to act as a respected global citizen, lending a hand in times of disaster, wherever that may be, the recent calamity in Beirut being a case in point.

Australia and China

Australia’s relationship with China has been firmly built on trade. Trade between the two countries accounted for almost a quarter of Australia’s overall two-way trade figures in 2019, eclipsing Japan at number two (9.7%) and the US in third place (8.8%). Australia’s continuously strong economic growth would almost certainly have been impossible if not for China’s insatiable appetite for the country’s minerals. On the flipside, Australians’ love of consumer goods has seen China account for around 19% of total imports, led by telecommunications and IT products[3].

While the trade relationship is symbiotic, the political relationship has been far from smooth. Confirming it does not shy away from making the tough decisions and asserting itself, Australia was the first country to ban the Chinese tech conglomerate Huawei from its new 5G telecommunications network, leading the Chinese ambassador to accuse Australia of discrimination. On this, the US (and later the UK) followed Australia, contrary to the narrative often portrayed in the media.

In April, Australia’s foreign minister, Marise Payne, announced a bipartisan push for an independent inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic. China reaction was unsurprising, suggesting Chinese may suddenly decide Australian products are of little interest, essentially threatening – and later delivering – economic sanctions. Australia has also expressed concern for China’s treatment of the Uighur minority and condemned its new national security law in Hong Kong, the latter move of which saw China retaliate by issuing a travel warning for its citizens in Australia.

These events have taken place alongside US aggression towards China led by Trump. He has been assisted by Hawkish Secretary of State Mike Pompeo who has been equally aggressive. At a speech on 23 July, Pompeo described Chinese President Xi Jinping as choreographing a “decades-long desire for global hegemony of Chinese communism”[4], an extraordinary statement.

Just four days later, any US hopes of an anti-China duo were surely dashed when, at a joint press conference with her American opposite, Payne made it clear that Australia would walk its own path saying, “The relationship we have with China is very important and we have no intention of injuring it”. As if that was not clear enough, she added, “We make our own decisions, our own judgments in the Australian national interest and about upholding our security, our prosperity and our values”[5].

Future regional stability

Despite vast distances making it one the most isolated countries on earth, Australia has played a vital role in the stability of its region. Future stability will depend in large part on this continuing.

The realignment of Australia’s foreign aid to its near neighbours is a key driver of this mission. Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s Step-up in the Pacific program has seen aid to the region lifted to a record AUD1.4 billion in 2019–20, more than a third of the total aid budget. Morrison told March’s G20 forum, “our Pacific island family must be a focus of international support”[6]. The maternalistic line was repeated in a ministerial media release where Payne described Australia’s “Pacific family” as “essential for our regional health and security and long-term interests”[7].

Morrison has acknowledged that Australia has at times taken its neighbours for granted, an admission perhaps spurred by China’s increasing interest – and notable inroads – in the region. One of the most significant events came in 2018 when it was revealed that China had approached Vanuatu about the possibility of establishing a military presence on the small island, alarming Australia and the US. A military presence in Vanuatu would put a Chinese military base within 2000 kilometres of the Australian mainland.

While the Pacific island nations have largely been spared COVID-19 casualties, many of their economies are heavily dependent on tourism. Many are already at the lower end of the socioeconomic scale and will be heavily dependent on aid to keep populations fed and sheltered, and in helping entire countries manage debt in the years to come. Fortunately, with a long history in the region and as its largest donor so far, Australia is well-placed to further its long-established success in economic diplomacy to help maintain stability in that part of the world.

Moving forward

More than half a century since historian Geoffrey Blainey coined the phrase “the tyranny of distance” to describe Australia’s growth from a British colonial outpost half a world away, the country is now a respected middle power, charting its own course more than ever. It has taken a global pandemic to put in an end to its world record 27 consecutive years of economic growth; it would take far more than that for Australia to adopt an isolationist strategy. It will continue strong multilateral engagement – not just with the US and China but other players such as the UK, the European Union, Japan and Indonesia – and an abundance of soft power in its arsenal. Its realignment of foreign aid priorities in recent years reflects an understanding of the reality that aid can be just as valuable a weapon in protecting and advancing security and broader interests as those of a more conventional nature. Crucially, those who argue Australia walks in lockstep with the US need go no further than recent events that have shown it will not be strong-armed into making decisions that favour its allies to its own detriment. With an outlook like this, perhaps it is time the perennial essay question was retired.

[1] https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/theres-no-i-in-team-but-is-there-a-us-in-indo-pacific/

[2] https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/suspicion-creeps-five-eyes

[3] https://www.austrade.gov.au/news/economic-analysis/australia-a-solid-trade-performance#:~:text=China%2C%20Japan%20%26%20the%20US&text=Rounding%20off%20Australia’s%20top%2010,%2C%20India%2C%20Malaysia%20and%20Thailand.

[4] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/07/27/pompeos-surreal-speech-on-china/

[5] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-29/ausmin-australia-united-states-china-relationship-diplomacy/12502222

[6] https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/pacific/australia-stepping-up-to-address-covid-19-in-the-pacific

[7] https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/marise-payne/media-release/responding-covid-19-challenge-pacific

© RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA