Interview by Daniele Lazzeri, chairman “Il Nodo di Gordio”

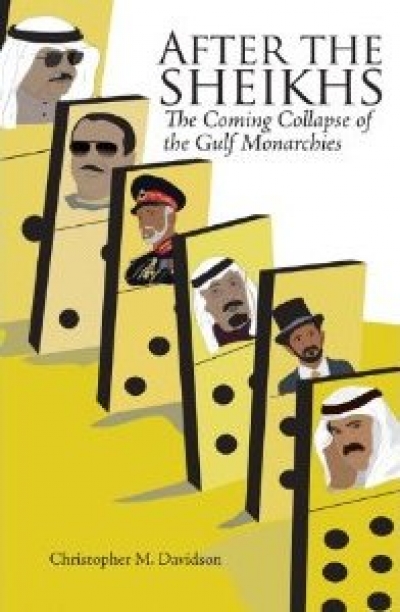

Christopher M. Davidson read Modern History at King’s College, University of Cambridge, before taking his M.Litt and Ph.D in Political Science at the University of St. Andrews. He has lived and worked in Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Beirut. Before joining Durham he was an assistant professor at Zayed University in the United Arab Emirates, first on the Abu Dhabi campus, then in Dubai. He is also a fellow of the UK Higher Education Academy and in 2009 was a visiting associate professor at Kyoto University, Japan.

His new book, “After the Sheikhs: The Coming Collapse of the Gulf Monarchies” was published in November 2012 in the UK by Hurst & Co.

In your last essay you foresee a future crisis of the Gulf monarchies, in particular Saudi Arabia, which, in general, is believed to have been strengthened by the Arab Springs. What elements suggest you the imminence of such crisis? And which impact would it have on the stability of the Gulf the fall of the Sheikhs?

Such a crisis will likely soon be upon Saudi Arabia, not only due to the shortcomings of its subsidy-based economy and rapidly increasing inability to offer sufficient benefits and employment to its growing number of citizens, but also due to the impact of powerful ‘super-modernizing’ forces on its society, namely social media and other technologies that are for the first time in the country’s history allowing large sections of its population to communicate with each other, unsupervised by state authorities.

As opposition groups consolidate themselves and continue to provide better organization and manifestos, they will seek to persuade the region and the international community that instability can be escaped, especially if they promise elected parliaments, adherence to international human rights conventions, and remain committed to existing international trade and investment partnerships.

Saudi Arabia and Qatar have exercised with their pan-Arab media – Al Jazeera and Al Arabya – a significant influence during the Libyan uprising and today in the Syrian issue. Is it possible, in your opinion, to speak today of an “Arabian” Soft Power, controlled by the Petro-Gulf monarchies?

Saudi Arabia and the UAE, waking up ‘late’ to the Arab Spring, have since tried to use their resources to exercise some control over the process, including the supply of arms but also including various ‘soft power’ approaches, hoping that the revolution in Syria will mark the final stand of the Arab Spring. Moreover, they have also sought to generate the image of an ‘Islamist winter’ in an effort to dissuade their own populations over the possibility of a moderate, democratic future for the Arab World. Qatar has of course been willing to promote Islamist groups in the broader region, sensing their likely election victories. But as with the other Gulf monarchies it draws the line at the Arab Spring extending beyond Syria and into the Gulf. Its support of revolutions in North Africa and Syria has not been reproduced in nearby Bahrain, for example, and it has begun to imprison a number of its indigenous activists in recent months.

The attempt, violently repressed, of a Bahrainian “Spring” has highlighted the problem of the Shiites subject to the Wahhabi monarchies of the Gulf. An issue that could lead to a conflict with Iran?

The Iran angle has been massively overplayed in the Gulf monarchies, mainly in an effort to portray any protests in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia as being sectarian and somehow ‘in league’ with Iran. This has been a useful strategy for keeping western allies on board in the face of a larger ‘Iran threat’ to regional instability. In reality, however, there are no formal links between the opposition groups in these countries and Iran. In fact, most of the outspoken Shia clerics in the Gulf subscribe to the political thought of Iraqi-based Shia leaders, rather than those in Iran. It should be no surprise that the Shia of Bahrain and Saudi Arabia have been the first to rise up against the monarchies, as they have historically been the most discriminated and impoverished sections of the population. Opposition movements in the UAE and Kuwait have fewer Shia involved, given the smaller Shia populations in those states, thus helping to deconstruct the sectarian argument about Gulf opposition groups.

Returning to your essay: the crisis of the Sheikhs, for which political systems would it open the door? There isn’t the risk of the affirmation of groups / religious-political movements even more radical and close to jihadism? And how would Washington and London see a possible regime Change in Riyadh?

As I discussed earlier, as the opposition groups continue to coalesce, gradually bringing various parties to the table – including Islamists, youth groups, tribal leaders, etc., we are likely to see broader-based movements which are well aware of the need to prevent radical elements coming to the fore, and well aware of the need to keep on board existing military alliances and international business links. In many ways, Washington and London have a lot less to fear from transparent governments that take charge in either constitutional monarchies (assuming peaceful transitions) or democratic republics (in more restive transitions, perhaps in Bahrain), as these administrations will likely have to prioritise anti-corruption measures, creating better regulatory environments, and honouring international human rights conventions.